View of Auckland, looking toward Rangitoto Island, from atop the windmill, 1901. Reference 1-W207, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries.

This post is a follow-on from

Part One. Updated 6 December 2023.

The 20th century story of the windmill on Symonds Street is one of lost opportunities to act to preserve the historical relic of days gone by. However from out of the public's realisation -- too late -- that something had been lost came the formation of the National Historic Places Trust, later New Zealand Historic Places Trust.

The windmill on Symonds Street had been a favourite spot for photographers to climb up and take vast shots of the surrounding views for almost as long as both the mill and photography had existed in New Zealand. George E Bentley, in

The Story of the Old Windmill (1898) wrote that both amateur and professional photographers used the top of the mill as their vantage point.

The mill, c.1909, from a postcard included with papers to and from James Wilkinson, ACC 285 Box 16, 117-121, correspondence re buildings 1908-1910, Auckland Council Archives. An uncommon photograph of the windmill without any sails at all. Note the name "J Partington", usually just above the lower doorway, is obliterated.

Sometime during 1903-1904, so a letter writer to the Auckland Star put it (Francis H Morton, 29 September 1908), Wilkinson had the sails completely removed, on the understanding that new slats were to be fitted. This didn't happen. Around 1906 James Wilkinson, then the owner-occupier of the windmill, chose to make some use out of the dilapidated building by converting it, effectively, into a potential tourist attraction.

Francis Morton, a music teacher by trade (possibly friends with Joseph Partington, who was always fond of music) urged the citizens of Auckland through the pages of the Auckland Star to preserve the old windmill. "I say emphatically, if we hare any love for our city, possessing so many objects and places of beauty, or if we have any respect for the memory of those who patiently and faithfully worked to found Auckland—the Corinth of the South -- then let us unitedly endeavour to raise an amount sufficient to purchase the present owner's interest—he evidently does not care to work or preserve the mill— and hand it back again to the former owner, Mr J Partington, son of the original builder, who is at present occupying the adjacent biscuit factory, and who would undertake to replace the sails, top gear and internal machinery, and guarantee to work the mill and retain it to the people of Auckland in that condition by deed. The public also to have free access to a scenic balcony on the top at any time." (15 July 1909)

Perhaps this helped to spur an approach Wilkinson made two months later to the Auckland City Council in the first of a number of lost opportunities that century, asking them to buy the windmill and surrounding land for £1000.

"I have lately expended a considerable sum in fitting the mill to make it suitable as a place from which a panoramic view of the City and its surroundings may be gained. I am also fixing a set of sails to the building.

"The view obtainable from the top which is now fitted with a balcony with seats and is easily accessible by a flight of stairs is, as your Council are aware, not to be surpassed in Auckland. The mill, as at present fitted, could easily be made a revenue-producing asset."

James Wilkinson to the Town Clerk, 2 September 1909, Auckland Council Archives

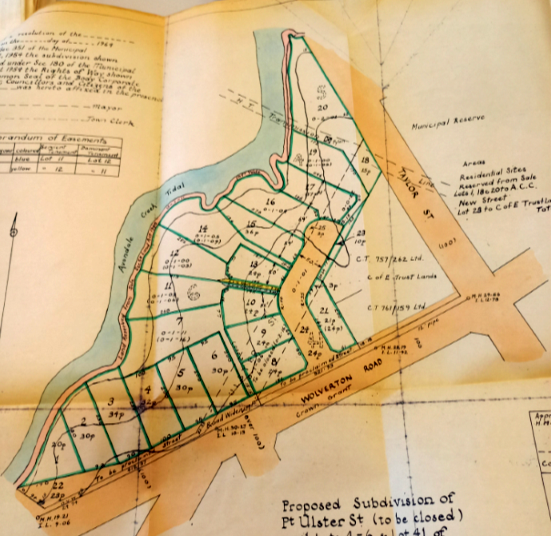

Detail from 1908 "City of Auckland" map, Auckland Council Archives.

At the time of Wilkinson's approach to the Council, the property was as shown in the 1908 plan above. The yellow lines mark the main mills property, with red dashed lines for boundaries between Wilkinson, including the windmill (blue circle) and Mill Lane, the two-storey brick stable from last century's dispute between Wilkinson and Joseph Partington (below the mill), and the large factory building (dark blue), a combination of wood, brick and corrugated iron, owned at that point by Miss Frances Dyne since 1905 (Wilkinson sold it to her; she was probably still Partington's housekeeper, so it remained business as usual for him). Advertisements appear in the Auckland Star from early October 1906, promoting "Partington's pure Whole Wheat Meal Biscuits" to be "obtained at Victoria Flour Mills and Steam Biscuit Factory, Symonds-St, opposite cemetery bridge." From early 1907, he advertised varieties of biscuit such as Round Wine, Afternoon Tea, Saloon and Cabin.Partington also regularly complained to the Council about Wilkinson's tenants in the house on Wilkinson's side of the boundary -- more often than not, the tenants engaged in the activities of a brothel (one case described in Police Court, Auckland Star, 12 July 1910).

It's possible that Wilkinson was trying to cut his losses by this time. He may not have been a well man -- three years later, he was dead, and the

Observer said kind words in his obituary:

JAMES WILKINSON, whose death took place in Auckland a few days ago, was familiarly known about fifty years ago, and long after, as Jimmy Wilkinson. He was engineer in charge of the machine room in the Daily Southern Cross. That was in the days when the paper was printed in the building still standing at the corner of Chancery Lane and O'Connell-street. The "Cross" was then published in an office at the corner of Queen-street and Vulcan Lane, where Dick Laishley, afterwards D. Laishley, and Tonson Garlick, founder of the great furnishing firm, were employed as clerks. Jimmy ruled the machine room with a rod of iron, and that was about the only sceptre which would have made his rule effective, for down in that room there were not only grimy faces but rough hands and unregenerate souls. When the Cross was sold to a company, Jimmy took up some shares in it. The company had a trying experience for some years, but under careful management, and able editorship, it was steadily regaining its lost popularity, when it was purchased by the late A. G. Horton, who, after a few months, entered into partnership with the Wilsons, of the Herald and the "Cross" ceased to exist.

Jimmy Wilkinson was strongly opposed to the sale of the concern, but he was outvoted. Jimmy was a man of kindly and genial disposition, yet of frugal habits, and his weekly wages at the Cross were supplemented by his emoluments as caretaker of the Pitt-street Methodist Church, a position which he held for many years. After the Cross became amalgamated with the Herald Jimmy took up practical engineering on his own account, acquired property, and made a comfortable competence. One of the properties he became possessed of was Auckland's oldest and most prominent artificial landmark, the Windmill. A few years ago, however, he sold it to a son of the original proprietor. Jimmy was kindly and genial to the last, and there are many who will be glad to meet him again when they, too, pass over to "the other side."

Observer 28 September 1912

The council's valuer reported that, in his opinion, the property up for sale (which excluded Mill Lane, for some reason) was only worth £658, land worth £408 and buildings (the mill and half of a cottage) worth just £250. Miss Dynes was also disputing with Wilkinson over a matter of two feet regarding the boundary between the windmill land and that of the factory. The council's finance committee recommended that the opportunity to purchase the windmill be refused, and Wilkinson was accordingly notified.

The following year in 1910, when Wilkinson put the property up for auction, the successful buyer was Joseph Partington, back from the dead financially and purchasing the old mill for £400.

Partington, still producing his health foods, described in advertisements in 1911 how the sails would be soon restored to the mill. This, however, didn't take place until 1915 after he took a trip to Europe from May 1914 to January the following year, when wind power looked like it would save him money running the factory. He extended the height of the tower by another 20-30 feet, in order to catch the winds above now taller buildings in the vicinity. The ornate cap (that which most who still recall the mill today would find familiar) was installed at that time, reportedly originating from off an old mill in Orston, Nottinghamshire, but dates in the report are not given and may refer to Charle's Partington's original mill. (

Auckland Star, 10 March 1925)

"The walls -- 3-ft thick -- are constructed of brick and cement mortar reinforced with steel, and some 3000 bricks were used in their construction. The sails, which have been remodelled, are 35 ft long and 9 ft wide. They are fitted with patent shutters, which act automatically, and are self-regulating. The total surface area thus presented to the wind is about 1400 square feet."

Auckland Star 24 May 1916

From 1915 until May 1925, therefore, the mill was back to its 19th century glory.

The mill in 1916. Reference 35-R1, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries

As seen from Karangahape Road in the early 1920s, when there was a gap in the development. Maple Furnishing Co had a hand in the later purchase and redevelopment of the mill site. Reference 4-8560, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries.

1 October 1923, from Mill Lane. Reference 1-W413, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries.

Then, in May 1925, a severe gale wrecked the sails so much that only two remained.

The violence of Tuesday night's gale proved too much for the old windmill overlooking Auckland from the vicinity of Grafton Bridge, and during a particularly heavy squall one of the four heavy wooden sails carried away and crashed to the ground. Owing to the fact that the mill is now electrically driven, the loss of the sail has not interrupted its usual activities. The mill, which is built of bricks, handmade from clay taken from the immediate vicinity, dates back to the early 'forties, when it was responsible for the city's flour supply. Some time ago the sails were dismantled and the place closed down. Ultimately, however, gas power was utilised, and the sails restored, with the result that work was recommenced.

Auckland Star 14 May 1925

Many eyes missed the whirling sails of the Windmill during the past week or bo during its temporary inactivity, due to the loss of one sail during a recent gale. This morning lovers of the old mill were pleased to see it in motion once more, though in a rather abbreviated form. Instead of the four great sails there were only two, and the result was rather like a bird with its wings clipped. Mr. J. Partington, the owner of the mill, was obliged to remove the third sail in order to get the two remaining sails to balance so that he might start work again. Three sails would have been lopsided, but the two opposite sails just balance, and enable the machinery to turn, with, of course, a diminished speed.

Auckland Star 26 June 1925

Despite reports that Partington was about to import more timber and reconstruct the sails, it never came to pass. By that time, Joseph Partington was 66. The mill property began the slow slide to dereliction again.

February, 1928, from Mill Lane. Note the motor garage with "Big Tree" advertising which had replaced a Lewis R Eady piano and organ wooden store. The needs of Auckland's passion with the motor car was already beginning to have an impact on the site's story. Reference 4-2282, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries.

Joseph Partington's idealised version of the mill never quite matched reality after 1924. Auckland Star 7 May 1930

Then, on 16 February 1931, came the great fire.

Auckland's oldest and best-known landmark, the windmill off Symonds Street, became a blasting inferno last evening, and over two hours elapsed before a necessarily depleted force from the city fire brigade station subdued the outbreak. [Another major fire had broken out in the city that same night.]

The sturdy brick walls, which have weathered the storms of nearly 90 years, still stand presumably intact, but only the skeleton of the picturesque sails and superstructure are left. The fire had its origins in an adjacent wooden building used as a store and garage, and the flames quickly spread to the mill, evidently bursting through one of the lower windows in the walls ... huge showers of sparks were shot into the night in eerie bursts like blazing confetti. The iron roofing became red hot under the impulse of the shooting, pent-up flames ... At last a portion of the roof gave way, giving the flames freer play to attack the sails and superstructure ... by the time the outbreak was quenched only the skeletons of the sails remained ...

The mill was divided into ten storeys. Machinery weighing about 15 tons was installed in the tower, while on the fourth floor there was also machinery weighing about 10 tons. A large quantity of wheat, valued at about £100, was stored on the upper floors. Bags and stores on the lower floors were evidently largely responsible for the brilliance of the fire in its earlier stages ...

NZ Herald 17 February 1931

Two or three cracks appeared in the new brickwork that was part of the upper 20 feet added by Partington in 1915. For the rest of its existence, the mill wore metal reinforcing bands at the top. The cap perished and had to be remade. Oddly, while the interior flooring had almost given way, the machinery within failed to smash to the ground. Once again, Partington pledged to the public that four sails would again grace his mill. Once again, that didn't happen.

Then, in 1936, there came another lost opportunity to preserve the mill. When the Metropolitan Fire Board looked around for a new site for the central fire station, Partington's land was on the short-list. So soon after a Labour Government victory in 1935 (Joseph Partington had a particular loathing, distrust and fear when it came to the Labour Party and any policies of nationalising the country's manufactories), this must have reminded him of the bad days of James Wilkinson's takeovers in the 1890s.

Unless the Auckland Metropolitan Fire Board can take it under some such legislative authority as the Public Works Act, neither the old mill site nor any of the property surrounding it will be available for the building of a new central fire station as long as its present owner, Mr. J. Partington, is alive.

"If they put a million pounds cash down on that doorstep, their money would not buy a foot of this site." declared Mr. Partington this morning, wagging a finger towards the doorway of the old mill. "Never since I inherited it have I ever sold a foot of this land, and I never shall. It is not a matter of money with me, it is a matter of sentiment, and I shall fight to the last ditch for the old mill."

Auckland Star 24 July 1936

Even though the Fire Board (who ultimately decided on their Pitt Street

site) denied any intention of demolishing the old windmill should they

get the site under the Public Works Act (the board stated plainly they

would have preserved the structure, somehow), Partington reacted. In September, Partington instigated a petition campain, as well as circulars to all Auckland's local bodies.

The concluding paragraph of the circular letter to local bodies issued by Mr. Wilis, on behalf of Mr. Partington, is as follows:—"I am not writing to your board for the purpose of discussing the suitability or otherwise of the proposed site for the fire station or to raise the question of the expense that would be involved, but I am asking for the support of your board in opposing the taking of the old mill or the land surrounding it for any purpose whatsoever. The preservation of the old mill has been Mr. Partington's life work and as his intentions are to benefit the community I have ventured to approach you for your support to help him carry out this laudable object. As the Fire Board has the necessary powers to take the land, it remains for public opinion to protest against the taking of the land, hoping that that will deter the Fire Board from carrying out its present intentions."

Auckland Star 9 September 1936

From out of the petition campaign came reports from local Maori members of the Akarana Maori Association that the mill was known to them as "Te Mira Hau", remembered from the earlier days as being a place where Maori were able to trade freely, bring in their grain and taking away the resulting flour. The story of the mill being loopholed in 1851 in readiness for serving as something of a fortress, during an incident where Maori from Waiheke Island landed at Mechanics Bay and performed a war haka came from an article published in the

Star, 23 September 1936. (The incident happened in April 1851. We know the mill was operating by August 1851, and may not have been quite finished by April. I've yet to see signs of any loopholes in the mill structure from that incident.)

Partington had his lawyer draw up his first will, bequeathing the property to the Auckland City Council when he died. The land he owned around the mill (from buying back piece by piece in the 20th century) would ultimately be Partington Park. This was viewed as a wonderful gesture at the time. No one recalled that Partington had had previously strong and negative views about city councils.

Evening Post 20 November 1941

In November 1941, old man Partington died. He was found dead slumped back in a chair at a table in his house, possibly from heart failure.

Slumped back in a chair in the kitchen of his home under the shadow of Auckland's oldest and most romantic landmark, the dead body of Mr. Joseph Partington, proprietor of the windmill near Grafton Bridge, was found by a tradesman at 11.30 a.m. to-day. There were the remnants of a meal upon a bare table beside which Mr. Partington had been sitting, his bed upstairs had not been slept in, and there was other evidence suggesting that death had come to the old miller suddenly …

A solicitor, Mr. C. H. M. Wills, who had been summoned by the police, assisted in a search of the house and discovered a hoard of money hidden about the place. Mostly in single banknotes and ten shilling notes, the money found represented a considerable sum. It was stuffed in envelopes with the amount scribbled in pencil on the outside, in fiat biscuit tins, tea canisters, and some bundles were carelessly tied with string, lying among a congested litter of personal odds and ends. Rats had gnawed a way through some of the bundles, partially destroying notes …

For some time Mr. Partington had been receiving treatment for valvular disease or the heart. He had never married, and was a recluse. For a long time—at least three years—he had lived alone in the two-storeyed house beside the windmill. Earlier a housekeeper had looked to his creature comforts. When the police examined the house to-day it was in a state of great disorder. Piles of newspapers and old magazines littered tables and furnishings. Dust lay thickly everywhere …

Gloominess and a great air of quietude is lent to the surroundings of the house by old trees, which practically cut the place off from the sun. Two dogs lay asleep in the backyard this morning when the police came, and on the front verandah an unopened milk bottle stood beside an ungathered newspaper.

The first Indication that there was the likelihood of money being found was the apparent carelessness with which a ten shilling note had been left protruding from a bundle of newspapers and periodicals, in the room where Mr. Partington's body was found. The door of Mr. Partington's bedroom upstairs was broken open by a constable, in the presence of the solicitor, and in the confusion of papers and letters in scattered heaps a search was begun. The top drawers of a dressing table were first rummaged, and small amounts of money were found.

A bar of iron was used to break open the bottom drawers of the dressing table, and inside large bundles of notes were found, amidst piles of correspondence, old photographs mostly of a personal nature, and the souvenirs of a long lifetime. An old medal "presented to J. Partington in 1874" bore the inscription, "H. Kohn's Cadet Prize." A gold locket contained a miniature portrait, perhaps of Mr. Partington himself, and a lock of hair …

Bookcases downstairs revealed other evidences of Mr. Partington's intense interest in windmills. Well-thumbed volumes of books treating of mills in lands abroad peeped out from among old volumes. Text books dealing with the technical aspects of flour milling were turned over in the course of the search. A vividly-coloured paper-back stood out amidst the time-dulled volumes of Victorian vintage. A reporter turned it, over. It was "The Windmill Mystery." Little would Mr. Partington think when he came by the book that he himself would provide in perhaps a minor way, another mystery of the windmill …

Auckland Star 18 November 1941

Stories and descriptions about the mill site and Joseph Partington himself in the final years from the fire to his death paint varied views. Author Ruth Park (1917-2010) in her autobiography A Fence Around the Cuckoo (1992) described the mill and its surrounds as a place of seedy dereliction at the end of the 1930s.

"The mill wasn't like anything in literature; it resembled nothing so much as a prodigious bottle tree, bulging at the base, tapering to two or three scraggy branches. There were the ruined sails, two, not four, for the mill had been burned before our family came to Auckland ...There was ... a ghostly croak and flutter from the sails, hanging down in splinters and gobbets from the forever-frozen cap ...

"All around the foot of the mill was confusion and disarray -- boxes and stove-in barrels, piles of rotting flour bags, a broken cart with its arms up in the air, And what appeared to be abandoned buildings, sheds, a storehouse, cottages ...

"[Inside] I found myself in a strange chamber, a machine room full of mysterious gears, with a monstrous shaft going straight up through the ceiling. In the discontinuous light from the street, I looked down on millstones, enormous, prehistoric, powdered palely with husks of wheat."

A woman named Muriel lived in the windmill, in a small room where a table was littered by papers and invoices. Apparently, according to Park, Muriel said she did a bit of bookwork for Partington in exchange for board in the small room up in the mill. Muriel did a bit of "the game" on the side, and when one of her clients attacked Park (sleeping on Muriel's camp bed due to heavy rain outside), the young girl ran out of the mill, into the downpour, then found her way to the old biscuit factory.

"It was a cavernous, mousy-smelling barn, full of rusty derelict machinery. In the mill's prime years it had been a biscuit factory."

From the

Auckland Star, 19 November 1941:

An intimate friend of 20 years' standing, Mr D Bradley ... presents a picture of a kindly old man who loved birds and music, but who insisted that what was due to him should be rendered to him ... "At heart Mr Partington was kindly," he said. "He told me on many occasions that it was his intention to leave the mill and its surroundings to the city I knew about the money he had about him in the house. He said he wanted to keep it handy to give to people who had been kind to him during his lifetime when he was dying. But he died suddenly and was lonely at the end."

The biscuit factory, once famous for the quality of its wares, is a jumbled mass of derelict machinery. When the miller had disputes with his workmen he closed it down. It has not been worked since.

£2350 in banknotes were found in wads all around Partington's house. More was found rat-chewed. Partington didn't poison the rats -- but he did believe, so one witness said, that the rats were Labour Party MPs transformed at night to cause trouble for him.

The 1936 will was apparently superseded by a later, 1940 will, made out with a different lawyer. This circumstance led to exhaustive hearing at the Supreme Court, because neither will was found in the house, apart from a hand-written draft. Some say the rats might have torn them both up as nesting material. Others thought that perhaps the 1936 will went into the bakehouse, and was eaten by Aucklanders as part of Partington's product. Others said that Partington turned against the council because of the rates demands -- had he thought to have rates relief by making the bequest? The Auckland City Council, despite having a signed letter on file from Partington himself, dating from 1936, confirming the bequest (I've sighted this myself) -- did not raise any contest at the court hearings in 1943. Yet another lost opportunity ...

The judge found that, in the absence of proof of will, Joseph Partington died intestate, and so granted Partington's cousins, nieces and nephews his estate. The land was soon sold to Seabrook Fowlds, a motor car importer.

Above and below: Architectural drawings of the windmill, 1945, from Auckland City Engineer's plans, ACC 015 /AKC 033, Auckland City Archives. The set includes some amazing pencil drawings of the mechanism within the mill as well, all set for a replica to be constructed. This, sadly, never happened.

The biscuit factory building was the first to be demolished, going sometime during 1944. The

NZ Herald on 21 April that year reported that the new owners "had taken steps to demolish an old shed and certain other dilapidated buildings on the property, and to dispose of some old machinery and other chattels. However, the demolition of the windmill was not contemplated and had not even been considered."

Demolition of the old Steam Biscuit factory building, from the NZ Herald 20 May 1944.

Four small millstones were apparently rescued from the factory and stored for a time at the Council's waterworks store at Western Springs, now the pumphouse at MOTAT. It is possible that the one

photographed at Howick Historical Village (scroll down on linked page) is one of these.

The mill, October 1947. Reference 36-P57, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries.

Now, we see more lost opportunities. Auckland City Council fostered the formation of an "Old Windmill Preservation Society" in March 1945, its purpose to raise funds by subscription to pay the cost of removing the entire structure of the windmill and relocating ... well, somewhere. At that point, it was estimated that around £3000 to £4000 would be needed; the campaign barely topped the £1000 mark in collected monies. Three sites were suggested: Parnell Park (now Sir Dove-Myer Robinson Park), the reservoir reserve on Upper Symonds Street, and Beckham Place Reserve in Grafton. The last was most favored, but nine residents petitioned Council against the idea, saying the mill "would interfere with sea and harbour views." (NZ Herald, 2 November 1945) That, along with the prohibitive removal costs against lacklustre public interest in supporting the fund to complete the project, meant that the Old Windmill Preservation Society foundered. In December 1945, the Council voted to take no further action.

Another lost opportunity: Seabrook Fowlds and Maple Furnishing offered, in 1947, to give the Council "all salvageable material which might be required on another site." (NZ Herald 14 March 1947) As the operation would need to be handled with greater care given that the preservation of as much as possible would be at stake, the companies suggested that Council provide the demolition crews, and so be able to give them special instruction. When the tenders came in at up to £3379, £1000 above city engineer's estimate, Council once more pulled out of the arrangement, deciding instead "to ask the owners of the Old Windmill to present the council with the machinery in the building and a few loads of bricks when the structure was demolished. The bricks are to be kept for inclusion in any replica of the mill that might be erected in the future and the machinery will be stored at Western Springs." (NZ Herald, 6 June 1947)

There may have been more dithering in the interim, but eventually Seabrook Fowlds and Maple Furnishing decided to proceed with the demolition of the windmill in late April 1950.

April 1950. The mill comes down. Reference 7-A5026, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries.

April 1950. The mill comes down. Reference 7-A5030, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries.

Auckland City Council received a letter from Maple Furnishing in late April 1950, advising that demolition was going to go ahead. They offered, as an eleventh hour goodwill gesture, to have their demolition contractors, Ivan Whale Ltd from Onehunga, save as many of the bricks, machinery as was possible. Even the great mill stones. Arthur Mead, the chief waterworks engineer, responded to the Town Clerk on 15 May 1950 (ACC 275/45-213A, Auckland Council Archives).

The only feature that appeared to Mead to be of "historic interest" were the mill stones. "These can be used in the Old Pumping Station at Western Springs which Council has already resolved to make available as a museum of historic machinery. The transmission gearing between the sails and the mill stones did not appear to me of particular interest, being merely rather clumsy mechanism of normal type ... also I cannot see much point in saving some of the bricks as they are only ordinary bricks ..."

Arthur Mead went on to have a street named after him (Mead Street, in Avondale), a small rail bridge on the

Rainforest Express line is named after him as well, and IPENZ have the

Arthur Mead Environmental Award. Perhaps more might have been saved had his eye not been so critical? We may never know, but his response certainly ended another opportunity.

The bricks, most of which from the original 1850-1851 construction and made from the clay of the site itself, so tradition tells us -- probably ended up as fill somewhere. The machinery from inside the windmill was, so it was discovered in 1978, taken to Onehunga, dumped in an Onehunga Borough Council quarry, and blown to pieces with gelignite, before being melted down as scrap for manhole and cesspit covers. The cap was probably worth just so much scrap metal. As for the large mill stones from the windmill, it looks like they had to be broken up by hand as they were being removed. (NZ Herald 8 October 1958)

April 1950. The mill comes down. Reference 7-A5039, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries.

Great public interest was shown in the demolition work being done on the old mill in Symonds Street yesterday. From early in the morning when slings were placed around the machinery previously used to revolve the top of the mill, dozens of onlookers arrived, watched for a few minutes, and departed.

Perhaps the most interested spectators were a group of elderly men who had either worked in the mill or had had intimate associations with its former owner, the late J Partington. While the donkey engine clanked and the huge wooden sails were slowly lowered to the ground they exchanged stories of early Auckland in general.

NZ Herald 29 April 1950

April 1950. The mill comes down. Reference 7-A5042, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries.

An oxy-acetylene torch was used to cut away the thick metal bands which were used to hold the sails in place, the operator swinging precariously in a boatswain's chair nearly 100 feet above the ground. Once the sails were lowered a rope was secured to the ornamental knob at the very top of the building and the galvanised iron dome was unceremoniously removed in one lift.

By mid-afternoon the work had drawn a small crowd to the scene and practically every window was occupied by people anxious to have a last look at one of Auckland's most historic buildings. All that remains is the grotesque, chimney-like brick shell.

NZ Herald 29 April 1950

April 1950. The mill comes down. Reference 7-A5043, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries.

What replaced the mill initially was a car park and container storage area, as seen in

this image from Auckland War Memorial Museum library. In 1978, though the land was up for sale again. When a bequest of $25,000 from Miss Myrtle Miller became available, the Historic Places Trust, Civic Trust, and the Netherlands Society all put together proposals to rebuild the mill either on the site (but the developers of the future Sheraton Hotel said no) or at least quite near, perhaps Grafton Cemetery. But it all came to naught -- and once more, due to cost: an estimate received of about $570,000 to rebuild the mill from scratch meant this last opportunity joined the long list of lost ideas for this particular heritage icon to be reborn.

So, where was the old windmill compared with today's landscape?

Overlay on part of 2006 aerial photograph, from Auckland Council website.

The Sheraton Hotel is now The Langham, and things have changed since the above 2006 aerial photograph, showing the main mill site, with the windmill circled.

Today, this is the view up Mill Lane from Liverpool Street. Today, there appears to be little if anything on the site indicating its previous historic value. The plaque originally set in a wall of the Seabrook Fowlds building by the Historic Places Trust in 1958 was removed when that building was demolished in the late 1970s, kept by NZHPT, given to the Sheraton Hotel where it was displayed for a time (the Steam Biscuit Factory and Partington's became part of the Sheraton's branding motif), then seemingly disappeared again with the change of ownership. I made enquiries last week, and it seems someone at The Langham has the plaque in safe keeping and is waiting for it to be picked up. As at 20 October, I notified NZHPT, and await word as to what has happened. [Update 12 March 2020 -- the plaque is safe and sound at the offices of Heritage New Zealand.]

The title of these two posts came from a 1902 poem about the windmill by someone simply called "Roslyn", from Auckland.

THE SONG OF THE WINDMILL.

"Ask of me if you would know

Stories of the long ago;

I, the watcher on the hill,"

Softly sighs the old windmill.

"I have heard the ringing cheer

From the coign of Wynyard Pier,

When the good ship o'er the foam.

Made the port from home, sweet home.

"I have seen the settlers' hopes

Planted on the ti-tree slopes,

Push their sturdy British way,

Hour by hour, and day by day.

"I have heard the night winds yearn.

For the hunting ground of fern,

Where they wandered wild and free.

From the mountain to the sea.

“I, that heard the tui sing,

Saw these dual cities spring,

Of the living, and the dead,

Lying now beneath me spread.

"Words are weak to point the change,

Far and near, within my range;

Domes, and spires, and chiming bells,

Roofs on roofs o'er vales and fells.

"Ye may wake, and ye may sleep;

Ye may laugh, and ye may weep;

In the present work your will,

I, the watcher on the hill

"Lose these noises, for, behind,

Ever whispers on the wind,

Music from the echoing vast,

For my youth lies in the past.

"Ask of me if you would know,

Stories of the long ago;

I, the watcher on the hill,"

Softly sighs the old windmill.

Auckland Star 25 October 1902

Reference 4-7141, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries

.

.